How should you approach the personal statement for residency?

Sometimes, it can be tough to know where to begin with your personal statement for residency applications. Many students get writers block, trying to think of the perfect and attention-grabbing opening, or closing flourish that will make them memorable. Instead, you should focus on making your essay personal, including details about what you have done and what has motivated you, and answering two fundamental questions that are required of every personal statement for residency. Namely, these questions are: what has motivated you to go into your chosen field? Secondly, what makes you a great candidate for that field based on your qualities and experiences thus far? Below, we have included a list of personal statements sorted by specialty from successful past applicants that will assist you in gathering ideas for a starting point, what kind of experiences past applicants have included, and thoughts for structuring your essay. Note that all of these essays have been submitted to schools from past applicants, and are only meant as a guide and certainly not meant to be copied (doing so would of course be plagiarism, and would likely hurt your application to many programs). However, having succeeded in residency applications for each applicant below, they can serve as a useful jumping-off point for how you will personalize your essay, discuss your interest in your chosen field, and display the qualifications and characteristics that are unique to you as an applicant.

How important is the personal statement for residency applications?

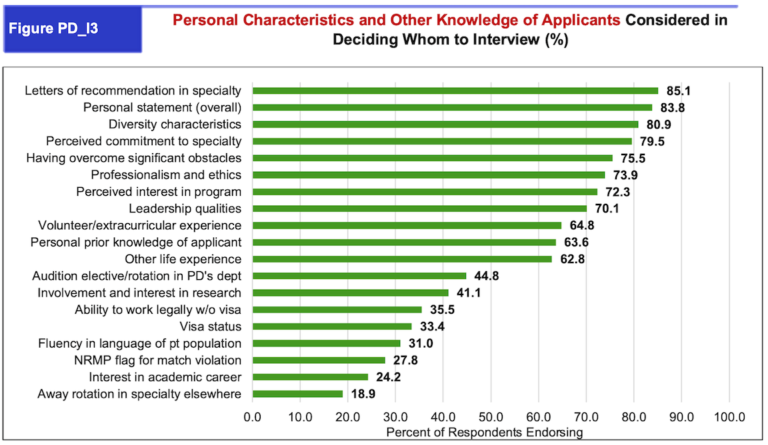

It turns out, very important. When considering the NRMP program director survey, it is the second most important factor when considering the personal characteristics of applicants (second only to letters of recommendation). You can view the table below, as well as the following link to go directly to the data for your specialty of choice.

1. Internal Medicine Personal Statement

My family’s ancestral home lies in the bustling haven of culture and energy that is New Delhi. My dida (my grandmother) was the embodiment of the city’s spirit. I remember her as she usually was found in the afternoons–sitting on the stoop of our stairs with waves of her grey hair ensconcing her face like a halo with a twinkle in her eyes and a wry smile as she cracked a witty joke.

During her final years, dida was diagnosed with a parkinsonism, and it slowly ate away at her body and spirit. There were many days where her smile had faded and her eyes had lost their luster. This was unfortunately an all too common occurrence after some of her doctor’s visits where she felt pushed around, rushed, and unheard. Towards the end of her course, however, dida started to speak more cheerfully after her doctor’s visits. It wasn’t because of any new medication slowing the progression of her disease; it was because she’d started to see a physician who took the time to empathetically communicate with her and guide her through her illness. Witnessing this positive impact of empathetic communication and patient-centered care sparked my interest in medicine.

While my dida’s experience first inspired my interest in medicine to provide empathetic care, my desire to pursue a career as a physician was solidified after my work in social justice endeavors. I founded my non-profit organization, Living Hope, to advocate for women’s rights in India and specifically combat the practice of female infanticide. Our efforts involved working with various international partners and raising funds to support education, housing, and health programs for girls and women in India. Through these endeavors, I saw how connecting girls to health resources helped them to secure agency and continue to pursue their educational and economic goals; this gave me insight into how medicine can be used to empower individuals and communities and achieve equity at large. My experience with Living Hope inspired me to pursue medicine with the goal of utilizing it as a tool towards sustainable, systemic change and reducing inequity within communities.

During medical school, I engaged in various efforts to develop myself in line with these goals. As a member of the Texas ACP Policy Committee and Texas Medical Association, I researched and developed policy proposals and interfaced with local, state, and national representatives to advocate for policy changes, such as Medicaid expansion, enforcement of improved standards of obstetric care for incarcerated patients, and strengthening public health safety networks. Furthermore, through my work at CommUnityCare, a local FQHC network, as well as with Fast-Track Cities, I engaged in advocacy efforts towards improving access to curative HCV therapy as well as worked to strengthen the local health system by designing novel programs to improve engagement and retention within the HIV and HCV care continuums. As the founding director of White Coats for Black Lives at my medical school, I engaged in community programming and fundraising efforts to mitigate racial disparities that were exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as in multi-pronged advocacy efforts focused on diminishing practices that furthered inequity within academic institutions and our healthcare system. Pursuing these endeavors further strengthened my desire to use my medical career as a platform for advocacy.

When deciding upon my specialty, I searched for a field that would allow me to pursue my goals of providing high-quality, patient-centered care while engaging in community programming and advocacy efforts designed to dismantle inequity. As the crux and origin of the medical field, internal medicine is my ideal field of choice to achieve these goals. In this field, I have had the privilege of witnessing physician leaders provide excellent evidence-based and empathetic care while advocating for their

patients’ needs on an individual and systemic level. Every day working on the internal medicine wards, I am inspired to broaden my knowledge, educate and support my team members, and continuously strive to provide my patients with the highest quality care possible. I seek to continue to do this as part of my residency training all the while working towards the overarching goal of developing sustainable health systems and dismantling disparities to achieve and promote equity across communities of all scales.

2. Internal Medicine Personal Statement

I’m a good listener. As a shy child, I felt more comfortable letting others do the talking. My role as a wild Irishman in a school play helped me break out of my shell. But the habit remained. I know my patients appreciate it. Rotating through the trauma service, I held the hand of a young man who cut open his leg jumping over a fence. He would be completely fine, but he was panicking as a resident closed his wound with sutures. I did what I do best; I listened. He revealed to me that during the ambulance ride, his adrenaline still flowing from what he suspected was a fatal wound (it was not), he proposed to his girlfriend and she accepted. The next day, he thanked me for being there for him. Even though he was afraid of needles, he didn’t hesitate to allow me to draw his labs after I told him I was a novice at phlebotomy. I still feel honored to have earned his trust, and all I had to do was stay silent and let him express himself.

I also love to ask questions. I’ve been doing it since I learned to talk; my parents couldn’t take me for a drive without facing fifty questions about how cars were made. In my former business career in strategy consulting, a partner at the firm called it my “superpower.” This skill has served useful to me in clinical medicine. I enjoy playing detective and trying to figure out what is ailing my patients. On my internal medicine rotation, a resident asked me to conduct a depression screen for an elderly woman who seemed “off.” Sensing there was more to the story, I deviated from the script and asked her if she felt safe at home. She confided in me that she did not, that her husband had angrily slammed a door into her, and that he had beaten her in the past. Sometimes it only takes one question to make a big difference in someone’s life, to provide them an outlet for their suffering, and to make available to them the resources that they need.

I dream about global health. It has been a major passion of mine since I started a nonprofit, Glasses for Guatemala, in 2012. Recycled eyeglasses are readily available in the U.S. and are very impactful to a person who has never had the opportunity to see with clear vision. When I visit Guatemala and engage my ability to speak Spanish to distribute eyeglasses to those in need, I feel an inner fulfillment that I have not experienced in any other facet of my life. I believe that in general, we undervalue the lives of other people in our world by remaining focused on what is right in front of our eyes: our routine, family, or job. I am determined to inspire others to think about the rest of the world. Living a life of service to others broadens the scope of my purpose in life and allows me to expand to become a welcome part of many other lives.

One last thing you should know about me is that I was raised to believe that those with the capacity to make a difference in the lives of others have a responsibility to do so. I changed careers because my personal experiences with ulcerative colitis helped me realize that good health is invaluable. During medical school, I learned that there is too much suffering in our world. I also learned that I could do something about it. I look forward to joining the field of internal medicine, where I can protect my patients from hopelessness and misery, and provide them with care and love. I aim to pair my clinical skills and my business background to become a health care innovator and a global health warrior. Listening to my patients will always come first.

3. Internal Medicine Personal Statement

It feels surreal that I am finally about become a doctor. My journey was filled with people who guided me through the unknown. Growing up, my 4 siblings and I were raised by my single mother in a low-income neighborhood in Houston. In high school, I didn’t know about higher education because I had no role models in my family. It was my Biology teacher, Ms. Brown, who sparked an interest in Biology that ultimately motivated me to go to college and become the first person in my family to graduate from college. After graduating, I wanted to help students achieve their academic dreams just like Ms. Brown did for me. Thus, I applied for the Teach for America program in order to serve students in low-income schools. I was fortunate to be placed at my old high school as a Biology teacher for students with Limited English Proficiency. I felt uneasy being on the other side of the classroom, but it was an opportunity to create hope in my hometown. I wanted to be the mirror that showed students that they could be successful.

It did not take long for me to get back in front of the classroom in medical school. I worked with other medical students to establish the Health Career Collaborative for the community during our first year. This program allowed us to mentor local high school students in a low-income area over health topics and was awarded the 2018 Excellence in Public Health award. We followed students from their 10th grade to their 12th grade and talked to them about their aspirations in working in health care. We were able to have in-depth conversations about health since we were at in their “territory” at the high school. In our third year, we had students identify health topics that they felt were not addressed by their school’s curriculum and then create a health fair that addressed those topics. Students learned about health topics such as mental illness, diet and exercise, and sexual health. They also learned professional skills such as how to reach out to organizations via email or over the phone. Giving students these skills could possibly set them up to be future community leaders, which will allow them to give back to their own communities by going into health careers.

During my Internal Medicine acting internship, I had the pleasure of working with a team that valued patient care, education and fun. Our attending would remind us to not forget the human side of medicine. I focused on treating my patient, not abnormal lab values, and justified every test I ordered so that it impacted my management. My senior resident allowed me to struggle in creating assessments and plans but would assist me when I needed it. The interns I’ve worked with made me feel like an intern and that motivated me to come to work every day. There also was a second-year medical student on our team who was beginning her clinical years. She reminded me of my experience jumping into a new system without much guidance since I was part of the inaugural class. I took her under my wing and guided her through the EHR, how to interact with patients, how to present to the attending, and how to study for the board exam. I loved being able to help her avoid the pitfalls I had so that she could help the team at her full capacity.

It’s important for me to choose a residency that will allow me to be part of a growing team. Texas is home for me. I want to be able to give back to my community, especially as an underrepresented Hispanic in medicine, because I would not have made it this far without the support of others.

4. Family Medicine Personal Statement

“You will complete this activity silently and independently.” Zeke talks; I’m ready for it. “Zeke, the directions were to be silent. This is your first warning.” Pencil-tapping, fake coughing and humming ensue, and I realize I’m not trained to give out warnings for actions I didn’t initially prohibit. This past year I taught high school chemistry in Fort Worth, Texas, through Teach for America. At first, I tried to do everything by the book, knowing there were tried and true methods to teach effectively. Trying to follow a formula to achieve success, I learned the vital lesson that building trusting relationships is necessary for communication. My knowledge of the content wasn’t an issue, but at the beginning of the school year, I was ineffective at reaching many of my students because of my textbook-teacher approach. Only after I had gotten to know my students more personally and developed their trust, was I able to effectively empower and give them tools to take ownership over their learning and therefore their future.

I see the same possibility in medicine. In the moments I interact with my patients and develop their trust, I will be able to empower them to gain an understanding of their disease and its treatment and guide them through the process of healing. Towards the end of my first year in the classroom, I was told that “there are few jobs in which you are handed a manual on the first day that explains how to do your job, because all of those jobs are now automated.” I believe that in order to be an effective teacher and physician, one must be able to build relationships and not solely rely on learned skills. Rita Pierson, a veteran teacher, said on a TED talk “kids don’t learn from people they don’t like.” I feel the same way about medicine; patients aren’t going to heal from a physician they don’t trust.

The desire to be a role model for my students was my primary motive to teach in a low income community. Having worked in this community for a year, I have witnessed lost opportunity and young people falling short of their goals, stemming in part from the lack of positive role models in their lives. Without leaders in place to procure a healthy community, attaining educational equity is improbable and the chances that my students succeed dwindle. Currently, there are many aspects of my students’ lives that I cannot affect. As a physician I look forward to having a more direct impact on their immediate health and well-being, giving them the chance to achieve their goals.

My second motive to become a teacher was due to the inherent role of education in medicine. I wanted to acquire the skills that accompany teaching so that I may use them as a physician. My kids entered the classroom unaccustomed to fully mastering difficult science concepts and therefore scared to attempt to learn them. By developing their trust, I played a role identical to the one doctors I will have with my patients, in which I will teach them about their diseases, taking the fear of disease out of the picture, just as I took the fear of chemistry out of the picture for my students. I will explain complex diseases in understandable terms and build trust with my patients so that they may take ownership over their own health.

In 1989, my family immigrated to Milwaukee from the Soviet Union and I was born three years later as the first natural American citizen in my family. Because my family grew up Jewish in the Soviet Union, their chances to study medicine were slim. As a result, there are few doctors in my family. The impact of this became evident when my mom’s first cousin, Lena, was diagnosed with lymphoma during my sophomore year of college. When she was diagnosed, she turned to my uncle, the only person in my family with experience in medicine. She wanted his input because she didn’t trust her doctors, so he met with her oncologists to see what he could do. Despite his efforts and years of training in infectious diseases, he said it was as if the oncologists were speaking another language and he could not convince Lena to listen to her doctors or start her treatment. Because of my experience in teaching and oncology research, I was able to convince her to pursue traditional treatment with chemotherapy rather than the non-evidence based alternatives.

I feel fortunate to have the opportunity to become a doctor and bridge my understanding of science with my ability to build relationships. I have come to realize that I have the responsibility to gain the knowledge necessary to care for, comfort and advise my loved ones when they encounter illness and to serve my students and their families as a practicing physician and role model. Reflecting on this past year, I learned that I am able to simplify difficult concepts, communicate them in a meaningful way and build relationships with people in the community I wish to serve; I wish to build these relationships in the clinic rather than the classroom.

5. Pediatric Residency Personal Statement

In the summer after my first year of medical school, I worked with two other medical students for 9 weeks in the southwest region of Uganda. Although I had expected the experience to be educational and positive, I had not anticipated that it would alter the trajectory of my life in the way that it ultimately did. Our biggest project was an effort to expand the district hospital nutrition program to more of the rural villages. This involved screening days in each village where we weighed and measured all of the children to evaluate them for possible malnutrition. On one of these screening days, we encountered a family that came to shape my view of myself as a person and a healthcare provider, as well as my role as a member of the global community. There was one boy, Izabayo (name changed), who we found to be severely malnourished by all measurements, but there were no parents around. The other villagers told us that he was 9 years old, and that his 11 year-old sister was his primary caretaker. This was disturbing information for several reasons. First, he was the size of a small 3 year-old. Second, an 11 year-old girl taking care of Izabayo and 3 other siblings was worrisome for the future health and wellbeing of all of them. We learned that their parents had divorced, and their mother left the village while the children stayed with their father. They told us that the father was sick and incapable of caring for the children. Seeing these 5 kids sitting there dirty, hungry, and afraid, the oldest girl doing her best to look and act like an adult, was one of the most heartbreaking experiences I have ever had.

We determined that Izabayo needed to be brought to the hospital for treatment of his malnutrition and further evaluation – he was clearly not of normal size or developmental stage for a 9 year-old. As we traveled back to the hospital, Izabayo sat with me in the car. I have held many children, but never before or since have I experienced anything like this. He latched on with an iron grip, and if my arms around him were even slightly slacker than his own arms around me, he would whimper and squeeze that much tighter. I was overwhelmed with feelings and questions. What is going on in his life that he responds this way? How long has it been since he has felt a caring touch? The dominant feeling that surfaced through all the others, however, was a fierce determination to do whatever may be necessary for this child. I had never had anyone need me the way he expressed he needed me, and I refused to betray that kind of trust.

This experience raised many questions for me about where and how I want to practice medicine. The story of this boy brought to bear most of what draws me to pediatrics. Firstly, the importance of families. I have always felt strongly about patients as part of wider networks and contexts, and I love that there is an emphasis on this built in to the field of pediatrics. I saw the impact of family situations in the case of this young boy. Further, this case involved the captivating science of human development. This is one of the things that most appeals to me about pediatric medicine. I want to learn as much as I can about how children come to have the adult bodies they will have, as well as become the people that they will be. What was happening that caused Izabayo not to grow? Was there a way we could now, or could have earlier, intervened to help him achieve his full potential? Which leads to another of the pulls I feel toward pediatrics – maximizing impact. In several ways, improving a child’s health is an investment that will grow over many years. In cases where a child has experienced some horrible misfortune, restoring that child’s health to baseline provides him/her with years of happy and healthy life that might have been lost. For children with chronic conditions, optimizing them at a young age can provide a life that is free of complications. And even in cases of perfectly healthy children with neither acute issues nor need to learn to manage chronic illness, a pediatrician can have an important influence. If we work to resolve, manage, and prevent disease, we can ensure that greater damage never has to happen.

I have always felt that the choice of a career should be based on what a person can do to improve the world. I think that it is also important that the career a person chooses be something he/she loves, because without passion the job will not be done properly. For me, these come together in the field of pediatrics. I am enchanted by the science of development and pediatric medicine, as well as the beauty of children themselves and the honor of being deeply involved in a family’s life. I also truly believe that I can have my greatest impact in improving the world by helping children to live the happiest and healthiest lives possible. I know that I want to invest my time, energy, and passion in children so that all of that work can develop and grow in and with them over whole lifetimes.

6. Emergency Medicine Personal Statement

For most people, coming to the ED means they are having the worst day of their life. They are scared, anxious, and uncertain about what is happening, how it will affect their future and that of those they love. All of this is compounded by the unfamiliar environment of the hospital.

One evening, a young woman came into the ED complaining of right lower quadrant abdominal pain.

The ED was busy, so she was relegated to a hallway bed near the work area where I was seated. As I approached her bed, I noticed she was anxious and clutching her boyfriend’s hand, her eyes widely observing the chaos around her. Following my history and physical I discussed with her what tests we were planning to run, and what conditions we were trying to rule-out. As we talked, I could see her becoming increasingly nervous. I did my best to put her at ease, explaining that being frightened is a valid response to her situation and that we would do everything we could to make sure that she was safe and taken care of.

She was understanding, and I left to check-up on my other patients. A couple of hours later, her labs and imaging came back normal. After speaking with my attending, we determined she was safe to be discharged with outpatient follow-up. I went back to her hallway bed and explained to her that while we did not have a definitive explanation for her pain, we were confident she was not having an emergency and could go home. Immediately, her expression changed; it was as if a visible weight had been lifted from her shoulders. She breathed a sigh of relief and thanked me for having taken care of her. Once she left, I took a moment and thought about what she had just experienced. Sitting in the hallway of a busy ED, watching personnel dash around to help suffering patients, her mind must have gone to the

worst-case scenarios, yet still hoping for good news. I’m humbled to think that I was able to make her feel better during such a stressful period.

I’ve heard ED physicians described as resuscitation and dispositions experts. In my opinion, some of our greatest interventions as healthcare providers include counsel and education. For that reason, I pursued a Masters in Educational Psychology during my third year of medical school. During this period, I spent time observing various teaching environments, constructing and executing lessons, reading literature on a range of education practices, and assisting in curriculum modifications at my medical school. One of the most important lessons I learned through this degree, that I will work to impart upon medical students and residents, is that there is a measurable difference in outcomes when acknowledging a person’s lived experience and emotions. Going into residency, I will use this degree to improve my teaching practices towards medical student, fellow residents and most significantly, my patients.

I wake up every day feeling privileged to be pursuing a specialty where I can gain someone’s trust and intervene, even if it isn’t through a code or an emergency cricothyroidotomy. Sometimes the needed intervention is making someone feel better during the worst day of their life. Whether a person is actually having an emergency or not, they are experiencing one when they come the ED. That’s why I love emergency medicine: I can make an impact on someone’s life when they are at their lowest. When I do this, I know I am making a difference and remember why I wanted to be a doctor in the first place.

7. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Personal Statement

After serving seven years in the military and three years as a civil engineer, I entered medical school looking for a sense of purpose directly interacting with others. I missed working toward a higher cause most in my professional life. In this final year of medical school, I know I have chosen a path to find both human connection and a sense of purpose.

Throughout this process, I have developed a new perspective on the struggles that our fellow citizens encounter with their health and the barriers to getting and staying healthy. I have developed a deep empathy for those in our community with unmet needs.

For my third-year research, I focused on people with amputations secondary to trauma. I was interested in this subset of limb loss because of the similar demographics to military amputees. Traumatic amputations typically occur in otherwise young, healthy, working and family-age adults with many productive years ahead. Throughout my research, I was fascinated with the portion of care that helped them regain their highest level of functionality. As I further explored the rehabilitation piece of the puzzle, I became increasingly interested in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

Throughout my PM&R independent elective in medical school, I discovered the broadness of the specialty. It is not restricted to one body part, but to a common goal at the nexus of many disciplines. Understanding the mechanics of body function was particularly appealing with my background in engineering. I am also drawn to the emphasis on an interdisciplinary approach to patient care, with strong relationships between physicians, nurses, occupational therapists, physical therapists, and the entire care team. I was impressed with my program and PM&R’s supportive and welcoming culture at all levels of leadership.

I bring a wealth of experience, maturity, and diversity of skills to your residency program. As an Army helicopter pilot, I led troops on multiple yearlong deployments to combat zones. I have worked under challenging circumstances with people from all backgrounds and abilities. After leaving the military I worked as a civil engineer, focusing on project management and water treatment. As a project manager, I refined my ability to schedule, meet deadlines and communicate across audiences, all within the context of providing services to the public.

While studying at my medical school, I started the Military and Sports Medicine Interest Group. Integral to this group was a mentorship program with middle and high schoolers at Ann Richards School for Young Women Leaders. This past year was also my tenth year as a board member for the Windy25 Memorial Fund, a national non-profit I helped create to support the families of America’s fallen service members. When not working, I enjoy spending time with my husband and sons, Owen (age 9) and Jack (age 6). We love exploring the country, swimming in the summer and spending time with our extended family.

8. OBGYN Personal Statement Example

26 asanas – 2 sets. 2 pranayama breathing exercises. 90 minutes. I stand in front of an endless mirror as the instructor says, “Focus on you and begin.” My home yoga studio sits in a recently gentrified neighborhood in East Austin. Most days, I am the only black yogi there. I cannot focus on that. I must focus on one point on my black body, while determined to fade the surrounding white bodies into the background. I realized early in my Bikram Yoga practice that the sequence and environment uncomfortably paralleled my experience as the only black woman at my medical school. Like the first time entering the 108-degree, 40% humidity yoga studio, I entered this journey of growth knowing that it would be difficult with nearly no knowledge of what “difficult” would entail.

I begin with standing deep-breathing pose – moving and claiming space in the nearly unbearable heat. My mind fails to meditate as I consider the instances that I was presumed to be lazy or disorganized as a student for no other reason that I could ascertain besides the color of my skin. Inhale, exhale. I tear my mind back to the present by the end of the second set. The instructor says, “Raise your arms directly in front of you. Stand on the balls of your feet. Focus.” I balance calmly while looking around to see if I’m holding the pose as beautifully as my white counterparts. Why does my mind often seem to wander here? I return to my breath – my muscles, tight and disciplined. “Hold your stomach in. Don’t move your eyes. You can’t even blink. You might fall out of the pose.” A wave of joy comes over me as I feel gratitude for what my body can do when it becomes inextricably linked to my mind – an invaluable skill to harness in training to become a practicing surgeon within the field of OB/GYN.

My Bikram yoga practice has taught me several lessons – most importantly, leaning into the feeling of discomfort. I moved away from my hometown in upstate New York to embark on a journey that I knew would catalyze significant growth. I am overwhelmingly grateful for the opportunity to develop into the physician and person I hoped to be from a young age. Since leaving New York to attend Davidson College, I have sprung into new and uncomfortable situations with vigor and eagerness, from virtually developing my own non-profit fellowship experience with a focus on marginalized populations in women’s health to creating a health equity student initiative from the ground up within my first year of medical school. Such experiences have allowed me to push myself and colleagues through challenging situations that call for resilience to failure and an unrelenting desire for improvement. Furthermore, they will serve as powerful narratives that I can share with the women I will take care of in my training and career, as well as with my co-residents. Irrespective of race or background, all women are vulnerable to social injustice – a reality that I will be particularly attuned to. My goal as an equity champion and women’s health physician will be to level the playing field through my patient interactions and mentorship of medical students from marginalized backgrounds.

Lastly, yoga has taught me an unwavering discipline that will prove formative to honing my skills as a surgeon and leader in health equity promotion. Bikram yoga beautifully parallels surgery and social transformation in that growth and improvement come from repeating the same sequence several times. Patience and gradual improvement are values I am familiar with, from blazing forward as a member of an inaugural medical school class to thinking critically about how my institution can grapple with and impact the seemingly impossible issue of structural inequities. I will not have to develop such attributes in residency training – I have them today. While I continue to ground myself in the reality that ameliorating health disparities will be a lifetime endeavor, I hold the patience and discipline to see the journey through to the end. I can only hope the feeling will mirror the Bikram’s final pose. I’ve come to do what I need to do and focused on what I can control in the process. Inhale, Exhale. Savasana.

9. Dermatology Personal Statement Example

As the oldest of four children, I gladly took on a caregiver role at an early age. I remember teaching my brother to read with the BOB Book series, helping my siblings with their homework and class projects, and driving them to school and swim practice as soon as I earned my driver’s license. My grandparents, a physician and a nurse, helped me to see medicine as a wonderful way to help others as a profession.

Realizing how many different disciplines of medicine interested me during clinical rotations was both exciting and overwhelming. My internal medicine clerkship resulted in a fascination with infectious disease, immunology, and oncology. I felt a deep satisfaction during both my general surgery and plastic surgery rotations when I could help fix a problem by working precisely with my hands. My visually oriented brain was captivated by the different ways that systemic diseases can manifest on the skin. I also learned that I loved meeting new people of all ages in primarily a clinic setting. Dermatology encompasses all of these interests, offering everything I desire in a challenging and rewarding career.

During several shadowing experiences prior to medical school, I noticed that many patients spoke only Spanish. I also saw the positive impact it made on their care when their physician spoke to them in their native language. I graduated college with a degree in Spanish so that I would be able to efficiently communicate with patients and their families in the language with which they are most comfortable. This also cultivated my interest in global health, which has led me to Guatemala, Madrid, and Peru to immerse myself in new cultures and to be of service to populations in need.

I am fortunate to be a director at C.D. Doyle Clinic, my medical school’s student-run, free clinic for the homeless and underinsured. Connecting with Austin’s most vulnerable population and being a resource and trusted provider for them has been extremely rewarding. My leadership at C.D. Doyle has allowed me to mentor undergraduate and medical students as well as develop educational components of clinic. I also implemented a collaboration between the Division of Dermatology at my medical school and C.D. Doyle to provide free skin cancer screenings and dermatologic care to those who would otherwise have no access to Dermatology services. This fulfilment from the past three years at C.D. Doyle has further affirmed my desire that education, mentorship, and community service be aspects of my career in Dermatology.

The curriculum at my medical school afforded me the chance to spend a year studying human-centered design from experts at the school’s Design Institute for Health. Travis County Emergency Medical Services wanted to find a clear identity for the non-acute, community health services they were already delivering. My team helped to define a cohesive mission for this community health model and developed a pilot program for a new reimbursement model. This experience taught me valuable lessons on the importance of understanding people before designing for them, as well as how to create, customize, and pilot solutions. My time at the Design Institute also taught me how to navigate complex organizational human relationships to create change within large organizations, especially in the face of resistance. I aim to leverage this unique skill set and perspective to help solve challenges that the field of Dermatology is facing.

I hope to train at a well-rounded residency program that serves a diverse patient population and values high-quality patient care, service, and leadership. I have also realized the importance of a strong support system, and I know that couples matching with my fiancé and having his support outside of residency will be important for me to stay engaged and working hard during our challenging years of training ahead. I am excited for the opportunity to devote the time and effort required to be an exceptional dermatologist.

10. Ophthalmology Personal Statement Example

The golf bag was half my weight, my feet were blistered, and my face was sunburnt. It was the summer of my 6th grade. I was beginning my first job as a new caddy at the local golf club. The club gave us strict rules: where to stand, when to talk, how to estimate and give yardage. As I started down the 18th fairway, I longed for an ice-cold drink and the air-conditioned caddy shack. I was exhausted finishing the round which started at 6:00 AM. Yet I was simultaneously energized with the empowering feeling of achievement. My excitement changed quickly when I heard the caddy master shout, “We’re short of caddies! I need a volunteer for another round.” That summer taught me commitment, discipline, and perseverance. At the time I took the job, all I could think about was the money I would earn. By the end of the summer and in the years to follow, I realized just how much that caddy experience influenced how I pursue some of life’s ambitions.

Now three years into my medical education, I appreciate even more those early lessons that have provided me the motivation for my career pursuit. My focus shifted from golf to my passion, medicine, and to finding a specialty that challenges and excites me. Initially drawn to ophthalmology for the precise surgeries, I sought opportunities for exposure prior to elective rotations and pursued research. Investigating the effectiveness of teleretinal diabetic retinopathy screening at area clinics created the perfect intersect for my interests in ophthalmology and health disparities. I analyzed statistics, led focus groups, created educational resources, and presented at ARVO and ASRS. Subsequently, our proposal to implement process changes based on the data gained clinic administration approval. This study incited a feeling of achievement, exemplifying the influence research exerts in modifying clinical practice.

My ophthalmology electives affirmed my commitment to this specialty. Assisting on many ophthalmology surgeries throughout my third year, my enthusiasm for the field grew through exposure to intraoperative successes and challenges. I appreciate the precise calculations of intraocular lenses and preoperative blepharoplasty markings combined with the finesse of managing proliferative vitreoretinopathy and DMEK surgeries. These vision saving operations appeal to my hands-on nature, while clinical encounters reaffirm my continued desire for patient interaction. No single moment rooted my interest in ophthalmology. The aggregate of patient encounters, learning ocular pathophysiology, and observing the significance of vision restoration for patients’ independence sustains my passion.

Outside of the clinic, I witnessed the spectrum of patient independence while volunteering each week during medical school at the School for the Blind. As a physical education assistant, the students and I bowled, tandem-biked and exercised in the gym. They never dwelled on their vision impairments. Their positive attitudes despite such challenges inspired me. Recognizing the significance vision holds in life, I grasped the impact of this career and the daily struggles of the visually impaired.

In retrospect, my greatest benefit from caddying was not physical nor monetary. Caddying taught me that discipline and determination can lead to the success of any challenge. My patient encounters cultivated empathy and clinical curiosity, driving my pursuit to maintain and restore patients’ vision. I am excited for the opportunity residency holds. I look forward to advancing my passion of ophthalmology and serving visually impaired patients.

11. Radiology Personal Statement Example

Taking the bus on the first day of my radiology rotation, I checked my email and saw the headline from a news bulletin: “CDC investigating cases of lung illness linked to e-cigarette use.” Since I was going to be rotating specifically with the chest radiology section, the title caught my eye. As the week went on, we saw two cases of vaping-associated lung illness – both of which were diagnosed by corroborating the patient’s clinical history of vaping THC oil with their imaging findings. At the end of the week, two CDC employees even visited the reading room to consult with the attending on other suspected cases that had been referred to them from across the country. The attending taught us about similar cases he had seen in the past and how the number of cases had been growing with the popularity of e-cigarettes. He also outlined how by working with other departments and institutions one might go about keeping a record of these cases to research and demonstrate the harm of e-cigarettes from a public health standpoint.

While I had already made up my mind to pursue radiology, this story captures what attracts me to the field. After initially being pulled in different directions, I decided to pursue radiology because it involves the intersection of multiple aspects of medicine that I find particularly compelling: the opportunity to form diagnoses through a combination of imaging and clinical information, the ability to work in quality improvement by regularly communicating with a variety of teams while building collaborative relationships, and the ability to teach in the classroom and clinical setting.

I was originally drawn to the field of medicine when I was young because of a “gut” feeling. However, as my reasoning evolved, I realized it was the ability to help patients by working as part of a team to solve specific diagnostic problems that motivated me the most. The radiologist is uniquely placed at the intersection of clinical information and imaging. In order to diagnose vaping-associated lung illness, the radiologist relied on details in the social history provided by the internal medicine team. While I observed this during a radiology elective, I also appreciated and demonstrated this attention to detail and ability to communicate during my clinical clerkships. For example, when I was on my internal medicine rotation, the team had a patient who kept presenting with asthma exacerbations despite her taking medications as prescribed. It was only when I re-interviewed her and realized that she had mold growing out of control in the house that we identified the root cause of her exacerbation. We were able to reach out and link her with a program that offers social assistance to Medicare patients to help solve her mold problem and hopefully prevent future admissions.

I am also attracted to the role the radiologist plays in communicating with other specialties and departments. This active communication provides many opportunities to pursue quality improvement within local systems- an interest that I plan to pursue in my career. Specifically, my work pursuing an MPH has demonstrated to me the importance of communication between all stakeholders when working in quality improvement. My capstone project was to implement mental health screenings and institute a referral pipeline for counseling at my medical school. We administered screening tools for depression and anxiety to all medical students and compared the prevalence of each across classes. We noticed an expected spike in both depression and anxiety during the clerkship year and while we will continue to survey each year to see if this trend continues across different classes, we have also held meetings with counselors and students affairs to create a sustainable plan that can ensure students receive easy access to mental health care. Any sustainable solution will require buy-in from counselors, school administration, the clerkship coordinators, and the students themselves. Similarly, if health care is currently faced with the problem of providers and various parties working in different silos, I believe radiologists are well-positioned to use their position at the intersection of imaging and clinical information to build collaborative working relationships and help bridge these gaps.

Medical education is another field that relies on building collaborative relationships and one that I plan to pursue both as a resident and attending. Teaching has been a common thread in my life since I was young. I grew up playing classical piano and eventually went to a performing arts high school where nearly half of each day was spent working with teachers and classmates – giving and receiving feedback. Prior to medical school, I taught high school chemistry at my former high school. Many of my students were intimidated by the math involved, and it was by focusing on the use of strategies and repetition that allowed them to make progress. However, before I could convince them to follow a method, it was important to build rapport and communicate that I had once been in their shoes. In fact, chemistry was my least favorite subject in high school – something which they found amusing but also encouraging. I find teaching to be incredibly gratifying, and I know that it is something that will continuously motivate me during my career. It was actually one of my first preclinical professors, a radiologist, who originally introduced my class to the field and became my mentor when I chose to pursue it.

In a diagnostic radiology residency program, I want to learn the skills and practices that will prepare me for a career in radiology, while also allowing me to help improve local systems and remain engaged in medical education. Finally, I hope to be a part of a collegial and supportive community. This sense of community is what I believe makes any individual or organization’s goals sustainable -a lesson cemented by my medical school experience. My graduating class has only 50 students, and we will be our school’s first graduating class. I’ve been fortunate to feel both supported and constructively challenged by my classmates as we’ve grown closer over the years, and it would be a privilege to be a part of a similarly supportive community again during residency.

12. Orthopedics Personal Statement Example

My earliest memories consist largely of helping my father in our garage while he worked on his cars. From changing the oil to grinding down exhaust pipes so that they would fit into his latest project, we did everything together. He taught me to measure twice and cut once, that you always needed the correct tool for the job, and that knowing why you are doing something is as important as knowing how to do it. And although I grew up in the garage, I also spent a significant time surrounded by medicine. At 13, I witnessed my friend break his arm on the baseball field and during my playing career, I had my own injuries and rehabilitation. In a high school magnet program in medicine, I shadowed various specialties in the hospital setting. My first case while shadowing was a total hip arthroplasty, and I was immediately drawn to orthopaedics. The same principles that my father taught me are prevalent in orthopaedics – surgeons can diagnose a patient’s problem and use their hands to treat it. And even more than treating a problem, regardless of who the patient is, we can help them regain mobility and live life to its fullest.

In the magnet program at my high school, I was mentored by a medical student – which supplemented the mentorship of my father – this mentorship was vital to my own success. Upon acceptance to medical school, I felt determined to give back to aspiring pre-med students. As co-director of the Health Career Collaborative program at my medical school, we mentored a group of seventeen underrepresented high school students from low socioeconomic backgrounds. It was gratifying to watch the students blossom from timid sophomores to confident seniors graduating at the top of their class with plans to pursue higher education and careers in medicine. Reflecting on the impact I was able to make on my mentees, I found mentorship incredibly rewarding and will continue to support aspiring medical professionals for the rest of my career. I am convinced about the power of effective mentorship and plan to take every opportunity to work alongside and mentor learners in a residency program.

Continuing my role as a mentor and leader, during my third year of medical school I pursued a dual-MD/MBA where I had the opportunity to lead a team and combine my love of medicine with my strategic and growth mindset. During my capstone project, I put into practice the teachings of both degree programs and designed a business proposal to bring a tactical athlete program to the community. Tactical athletes (e.g. military, police officers, and fire fighters) must always be operational under the most challenging of circumstances. As such, they incur a vast number of musculoskeletal injuries, many of which are preventable. Working across a multi-disciplinary team, we designed a program that could save the city hundreds of thousands of dollars and made a successful proposal for plan integration. This experience of combining business and medicine while making an impact in my community is something I hope to continue throughout my residency.

Every time I scrub into cases, I am reminded of my father’s garage and the lessons he instilled in me: the importance of technical skills coupled with preparedness and intellectual curiosity. I am eager to utilize my work ethic and team orientation that I learned on the baseball field to diagnose and treat patients as they embark on their journey towards mobility. Through my desire to be a mentor and my MBA mindset and business acumen, I am confident I will be an actively contributing and effective orthopaedic surgery resident. I am constantly reminded to give back what was given to me, and I am excited for the opportunity to practice my passion as an asset in your program. Thank you for taking the time to review this statement and my application.

13. Anesthesia Personal Statement Example

The pitch of the anesthesia machine steadily became lower as the patient’s oxygen saturation started decreasing. A loud beeping alarm became apparent as his blood pressure began to fall. Just a few minutes ago, the patient was sitting up and talking, and the next, the situation changed. Through the intensity and urgency that had developed in the OR, the anesthesiologist at the head of the bed maintained a calm demeanor. He had one hand on the bag and the other on the face mask, applying pressure and oxygen for the patient while running through the “ABC’s” of critical care. As the patient’s pulse began to disappear, compressions were started, and the anesthesiologist began to delegate tasks like a conductor in an orchestra. This experience is one of the many reasons that motivate me to pursue a career in anesthesiology.

Watching as the anesthesiologist was able to manipulate and tweak the ventilation machines to minute detail in order to keep the patient stable during surgery was awe inspiring, especially with having to understand the physiology that is in a way unique to each patient. This is further exacerbated by the plethora of pharmacotherapies that are utilized by the anesthesiologist depending on context and situation. This mastery of physiology and pharmacology is something that I aim to strive for.

Anesthesia piqued my interest when I was first exposed to the specialty during the 2nd year of medical school. In a way, this is due to the similar characteristics and traits shared between my experiences with teaching and anesthesia. For example, the importance of first impressions is invaluable for both professions, the ability to organize and delegate tasks, and adaptability to changing circumstances in real-time.

Before enrolling in medical school, I was a science teacher for an underserved high school in Las Vegas. During clinical rotations, I was determined to utilize the skills that I had learned as a teacher to create a foundation and help make me a better clinician. One of which is the importance of first impressions. The teacher’s role on the first day of class is to develop a trusting and respectful relationship with the students to achieve student success. This is through individualized planning and student-centered goals. Anesthesiology offers me the opportunity to use these same skills to develop a trusting relationship with patients in a short amount of time. Furthermore, as no two students are the same, no two patients are the same. Anesthesia allows me the ability to factor in each patient’s uniqueness such as their anatomy and physiology to provide patient-centered care and comfort. Whether that’s through providing an epidural during delivery or a femoral nerve block for knee surgery.

During college I have been interested research and had the opportunity to pursue an MPH while in medical school. Through this MPH I was able to further improve my knowledge of conducting literature review and asking research questions as well as understanding epidemiology and population health. My project during my MPH focused on conducting a quantitative analysis for the use of Ketamine to treat suicidal ideation. In this project I was able to conduct interviews with important stakeholders as well as analyze clinical data to answer a research question. This is one of my goals as an anesthesiologist, to utilize the techniques and skills that I have learned during my MPH to further answer research questions.

Before starting clinical rotations, I had heard of the term “patient-centered” care, however did not know exactly quite what that meant. Over the course of the 4th year I would embrace the term as the foundation to how I would help to provide care now and in the future. This ranged from updating families about the patient’s care to bringing a warm blanket. Furthermore, incorporating multidisciplinary teams involved in the patient’s care such as through interfacing with the patient’s nursing team and the radiology and pathology team. I am interested in continuing to utilize patient-centered care as an anesthesiologist as a holistic and multidisciplinary approach both in the OR and in the consulting room before.

14. Psychiatry Personal Statement Example

I was not looking forward to my rotation in the psychiatric ward and regarded this as only as a necessary obstacle that I had to surmount in order to qualify as a doctor. However I became fascinated with the patients, their conditions and treatments. I soon realized that every patient was person who had goals and hopes a person who had a family and friends who loved them and anxiously awaited them to emerge from the mental ‘maze’ in which they found themselves. My apprehension was replaced with empathy, sympathy and a longing to be of some help.

Following my internship, I worked in the medicine department of a missionary hospital. There was no psychiatric department and our department was responsible for dealing with psychiatric patients. The cases we handled were not extreme, being mainly fairly mild depressive conditions, but I was involved in counseling some of these patients and found enormous satisfaction in doing so. I also identified psychiatric illness in, apparently routine, ER patients on several occasions by careful observation. When counseling, I learned that understanding and responding to non-verbal signals is a very important skill in dealing with distressed patients and is one that I naturally possess and hope to develop further. I have always sought to care about my patients as well as caring for them and I believe that this is especially important in psychiatry.

Ultimately, I hope to be involved in research and teaching. With this in mind, I joined an MD program in Pharmacology and I had started a thesis project in psychiatry when I obtained permission to enter the US. The study related to the efficacy and safety of Tianeptine compared to Sertraline for treatment of major depressive disorder. My work also involved the study of phsycopharmacology and I began to think back to my internship work with psychiatric patients and my interest in psychiatry was re-fired. Once in the US, I considered my choices carefully and decided to pursue psychiatry rather than pharmacology.

One great difference between psychiatry in India and the US is that it is rare to see dementia patients in India. In my culture, the family generally takes full responsibility for the care of their elderly, dementia sufferers are indulged and cherished in a familiar environment and medical intervention is sought only in extreme cases. In the US the situation is very different and the effects of aging constitute a growing challenge as the elderly grow in numbers and as a proportion of the population. Their problems being compounded by the fact that they often find themselves in unfamiliar surroundings once they lose their ability to care for themselves. Psychiatry has a great and growing responsibility in this area of work and is one that greatly interests me.

I realize that understanding the cultural background of a psychiatric patient can hardly be overstated. I have worked and studied with people of many cultural and social backgrounds and am eager to extend these experiences and familiarize myself with cultures that are new to me.

I am aware that there will be many well qualified applicants for residencies in this fascinating specialty. However I believe that I am an exceptional candidate. I am diligent, intelligent with a capacity for hard work; I have substantial experience of providing medical care, including the counseling and identification of psychiatric patients, in a hospital setting; I have carefully prepared myself for the program, having been an ‘observer’ in US hospitals. However my main recommendation is a passion for psychiatry that I look forward to demonstrating in the program.

15. Urology Personal Statement Example

When I first began on my path in medicine, I knew only that I wanted to use my past experiences in nutrition to enrich my practice, in whichever field that that might end up being. Naturally, many friends, coworkers, and whomever else learned I was applying to medical school encouragingly told me how useful my background as a dietitian would be for counseling patients. This buoyed my confidence and left me feeling as though primary care would be the obvious choice. Having had nobody else in my family attend college, let alone medical school, granted me little insight into the scope and intricacies of each specialty.

One encounter at the outset of my journey is more memorable than any other. My first medical school interview was with a physician faculty member, a surgical oncologist. He was also kind and encouraging, but in a move I didn’t quite expect, he tried to recruit me to surgery. He discussed the importance of nutrition in surgical outcomes, of preparing a patient physically for a taxing surgery, and how my background would serve me well as a surgeon. Although I ended up attending a different school from where this interview took place, I have encountered different surgeons who also value the role of nutrition. This has afforded me opportunities to pursue research in this area, such as preoperative strength training and nutritional supplementation for frail individuals to give vulnerable patients the best chance at postoperative success.

This exposure also fed into a strong passion for research, a passion for which I have pursued continuous self-improvement. The unique curriculum at my medical school enabled me to increase my understanding of statistics and research design through completing a Master’s in Public Health during the third year of medical school, which I have enjoyed translating into tangible research projects. Satisfied that I could apply my past skillset to my future in a broader way than I had imagined, I have allowed myself to fully embrace that I could only see myself in a specialty that is, at its core, surgical.

As I have discovered urology, I have enjoyed the ability to use nutrition, but also to intervene surgically to drastically improve quality of life. An emerging area of interest in endourology has led me to learn more about the links between nutrition and stones. I am drawn to helping patients make small changes that can have a major impact. However, if those lifestyle changes aren’t enough, I can also be the one to intervene surgically to help my patients have positive outcomes. It is perhaps the ability to help my patients anywhere along that spectrum of treatment that they may need that I find most exciting. Because as much as I value what I have gained from my past experiences, I love the mastery required and the thrill of the operating room even more.

Whether it be andrology, oncology, endourology, or reconstructive surgery, I have loved every aspect of urology to which I have been exposed. I have been repeatedly impressed with how respectfully and caringly my urology mentors navigated sensitive topics and built rapport with their patients. I have been impressed with their comfort in deciding when to cut and when not to cut, and how to involve the patient in this decision. I have perhaps been the most impressed in working with them during surgery, observing their technical skills over a wide range of surgical approaches and learning from them. Although I know I have barely scratched the surface in the field of urology, what I have seen has laid the foundation for the type of physician and surgeon I hope to become and cemented that a career in urology would give me the greatest fulfillment. The wide breadth of practice, of patient population, and pathology is interesting and alluring, and I look forward to seeing where a career in urology will take me.

16. Radiation Oncology Personal Statement Example

I could tell Mrs. H was upset by observing her body language as she entered my classroom for her son’s parent-teacher conference. After three years of teaching chemistry and physics through Teach for America at a large Title 1 public high school in Dallas, I was no stranger to communicating with upset parents and students. Fortunately, I had good news – her son was doing an excellent job as a sophomore in my chemistry class. As we sat and went over his exam scores and performance, which were spectacular, tears began to flood her eyes. Surprised by her reaction, I asked if there was anything else going on. She had just been diagnosed with breast cancer, and she was only thirty-nine years old. As a single mother, she was overwhelmed by her new diagnosis, by her complex treatment plan, and by the fear that she wouldn’t be around to care for her children. I realized that despite my years of volunteering and research in medicine, I was as bewildered by these next steps as she was.

Later, in medical school, I would be reminded of my conversation with Mrs. H while I pre-rounded on a patient who had recently undergone surgery for her breast cancer. To my surprise, she stated that the most frightening part for her was yet to come. She knew that she would need to have radiation therapy to increase her chances of being cured, and yet she was terrified of what it would entail, whether she would be able to afford it, and what its side effects would be. I still felt unprepared in the face of these questions, and I decided to shadow at a local radiation oncology clinic in Austin to broaden my perspective.

I found it rewarding to work with a unique patient population, and it was fulfilling to help guide patients through some of the most difficult moments of their lives. I was fascinated by the variety of radiotherapy options, the treatment planning involved, and the technical skills required to leverage this incredible technology to prolong life and relieve suffering. I was excited to delve deeper into the field and, having witnessed firsthand how patients like Mrs. H were confused by the complexity of radiation therapy, I knew how I could start. Employing a distinct perspective from my years as a teacher, I collaborated with radiation oncology residents and attendings to publish patient-centered education articles discussing the potential early and late toxicities of radiation therapy.

To continue developing my rising interest in radiation oncology, I also thought of ways to utilize my research skillset to further contribute to the field and advance treatment options for patients. I investigated the latest innovations in surgical radiation oncology that have occurred within the past ten years, studied the impact of cancer care on financial distress and quality of life in low-income populations, and dedicated my third year of medical school to full-time basic lab research and the discovery of novel immunotherapy combinations in colorectal cancer. Through this last effort, our team at Livestrong uncovered a unique synergy between immune-stimulating compounds, which we presented at national cancer conferences across the country.

While growing in my passion for research and patient care, I retained my dedication to teaching and community involvement. I found two classmates willing to spearhead the organization Health Career Academy, which provided mentorship for local Austin public-school students and assisted them in addressing health issues important to their community. Among these was the impact that cancer can have on families, which many students were eager to discuss and present at their public health fair. Continuing my work with patient education and community support initiatives are chief among my future goals as a clinician. Through my training as a radiation oncologist, I hope to grow in my ability to contribute to advancements in the field, cultivate my enthusiasm for teaching, and provide empathetic care focused on improving the lives of my patients.

17. Surgery Personal Statement Example

I come from a long line of military and manual labor. Spending the majority of my formative years in rural Parker County, Texas, I had a seemingly equal chance of becoming a roughneck on an oil rig than I did pursuing the path to medical school. If I had not had an intelligent and influential older brother to serve as a role model for academic success; I might have been pulled even further toward manual labor like my peers at the time. Being a first generation academic in my family, it seems as though I was building the bridge as I was walking across it. However, I have been told by those closest to me that being a blue-collar man on a white-collar pathway has given me a unique perspective. This perspective is likely best described as one of mental toughness and has certainly kept me even keeled through the ups and downs of life and medical training.

As I went through clerkships, I quickly learned that surgery was gritty. The residents were on the grind all day and often into the night. This was the closest I had seen to the roughneck, manual labor mentality that I was familiar with. The surgery residents were putting in the hours for their patients when they could have gone home. They were unafraid to take ownership of the outcome of case, no matter what that outcome might be. The pecking order and overall mentality of surgery was the first time in medical school that I felt like I truly fit in and was disappointed when it ended.

I had at that point confirmed I wanted to be a surgeon, but I needed to figure out what type of surgeon I was going to be. I mulled over a few different ideas, but I was immensely drawn to vascular surgery. I really liked the skillset that was required to successfully perform a vascular procedure. It requires a great deal of finesse and creativity at times. No two patients’ needs are exact, and the multitude of available treatment modalities allows the vascular surgeon to tailor the best option to the patient. This is an extremely attractive aspect of the field for me.

I also enjoy the patient population. Vascular patients are often particularly vulnerable and sometimes have an added layer of personal or social difficulties. I have received feedback from residents and mentors that I connect very well with these patients. I think this might be due to background and upbringing. My family, for better or worse, is less removed from many of the unfortunate attitudes and circumstances that vascular patients contend with. I think this has allowed me to relate and understand their difficulties on a very basic and human level. The ability to build long-term relationships with these patients is another major draw for vascular surgery in my eyes.

As for long-term goals I want to be an effective, efficient, and masterful vascular surgeon in my future career. Although I definitely have strong research interest and enjoy teaching, my primary goal is to be the best vascular surgeon that I can be. In training I hope to take care of an extraordinarily high volume of patients and achieve proficiency in both open and endovascular techniques. I am looking for a program that will aid me in this goal and provide the best training possible.

18. Neurosurgery Personal Statement Example

I grew up on a farm in a town of less than 2,000 people in central Texas. My father was a pecan farmer, as was his father, and taught me the principles of the ‘family trade’ from a young age. Throughout my childhood, I would make the half-hour drive home from school and labor atop a tractor for hours. In my spare moments, I discovered an old guitar in the attic and began to slowly teach myself basic chords and scales. Over time, I became skilled in jazz, blues, rock, and country styles. With a modest income from working for my father and at local livestock auctions, I upgraded and augmented my musical equipment. For the first time in my life, I developed a unique skill out of an organic passion.

I entered the medical school with an undifferentiated interest in all specialties. Much like my decision to pursue a medical career, I discovered a passion for the neurosciences early. The unique anatomy and conceptualization required to understand the central nervous system drew me to the neuro-specialties. What was most memorable for me was a faculty neurosurgeon’s lecture on the optic pathways and his explanation of the neuroanatomical relevance for surgical intervention. After experiencing other specialties through my core clerkships, I realized the real-time manipulation of neuroanatomy, the interface between the surgeon and innovative technologies, the rapidly expanding sphere of treatable neurological disorders, and broad opportunities to contribute to meaningful research in neurosurgery was unparalleled.

During my second year, I rotated on the neurosurgery service as a clinical elective. It was here that I was first exposed to the wide variety of neurosurgical disorders. One patient was particularly memorable and cemented my decision to pursue neurosurgery; a young man was devastated to learn that although his newly-diagnosed astrocytoma was low grade, it would likely undergo ‘malignant transformation’ to a grade III or IV tumor. During surgery, I witnessed firsthand the expertise necessary to achieve gross total resection for this patient and understood the privilege of providing such a high level of care to such a precarious and fascinating anatomical region. I was inspired with the unique impact the neurosurgeon had in this patient’s life by guiding him through a difficult diagnosis and subsequently performing a challenging surgery. What is more, the discussions with the patient regarding his prognosis prompted me to explore the field of neurosurgical oncology and the methods for predicting tumor progression, to better serve this patient population.

With the support of neurosurgeons at my institution, I connected with a distinguished mentor at an outside institution who graciously allowed me to spend nine-months in his lab to fulfill my research distinction. I entered the year with almost no prior research experience and completed seven projects. During that time, I learned from scratch the skills necessary including advanced survival statistics and computer programming to build predictive machine learning models. This year provided me with dedicated time to develop a scientific mindset and learn research skills, and also inspired me to pursue an academic career. By delving into the growing field of computational ‘omics’ and the applications to neurosurgical oncology, I carved out an organic research interest I intend to develop in residency training. I consider it a high privilege to serve in the ever-evolving sphere of neurosurgical practice and I am thrilled at the prospect of becoming a part of it.

19. Plastic Surgery Personal Statement Example

After releasing the last of four tendons from adhesions, we woke the patient. The dominant hand that before had limited flexion could now make a complete fist. The patient joyfully exclaimed they had been given hope back. His trade required the use of his hands and without proper movement, he had not been able to perform his job. In one surgery, this patient went from unemployable to optimistic. In one hour, this patient’s quality of life was drastically improved. It was then that I knew I wanted to be a plastic and reconstructive surgeon. As a future surgeon and leader in this field, I aspire to not only excel clinically, but also push the success of the field forward and be a mentor and teacher to others.

The field of plastic and reconstructive surgery is constantly changing and developing new, innovative techniques. I aspire to advance knowledge forward and develop techniques that change patient care within the field of plastic surgery and beyond through research. While doing research in medical school, I discovered the field of plastic surgery would benefit from more high quality research, as many of the techniques performed in surgery do not necessarily have evidence-based research to back them. As a naturally inquisitive person, I had many theories I would like to test, but did not know the proper way to implement them. During my third year of medical school, I decided to obtain a Master of Public Health degree to learn more about proper data analysis and how a population can be analyzed. I hope to use what I have learned to create high quality projects that improve patient care and ensure these changes can be implemented with the appropriate level of evidence. Having a forward-thinking and organized mindset will enable me to adhere to the long-term goal of these projects to see that they are brought to fruition.

As a first generation college student, I realize the value of education. At a young age, I developed a love for learning and the grit necessary to push myself to excel in school and graduate as valedictorian. I knew that going to college was my chance to open a larger number of doors for myself and that doing well in school would provide me the means to do so. Since an education has been lifechanging for me, I naturally developed a desire to bring this gift to others through teaching. Before medical school, I taught high school chemistry. I set high expectations for my students that I knew they could meet and provided active learning environments for them to practice in. Immediately after learning the material, the concept was applied in a hands-on way and students used spaced repetition to retain what they learned. I emphasized the importance of setting small, attainable measures to serve as stepping stones on the path to their overall goal. Serving as a mentor to these students and helping them achieve their full potential was a role I thoroughly enjoyed and I cannot imagine myself in a practice without the ability to continue educating.

The journey to a career in plastic and reconstructive surgery is extensive, with many uphill battles to come. However, I am confident in my ability to see the greater picture and perform whatever role is necessary to benefit the patient and surgical team. A consistently evolving curriculum and a willingness to implement change are key aspects I seek in a residency program. Avoiding complacency prevents burnout in physicians and is how medicine will continue to advance. I seek a residency program that allows me to work diligently to improve my clinical, research, and teaching skills to be a competent ambassador of the program.

20. Neurology Personal Statement Example